The following corresponds with my presentation at PAX East. The Power Point slide show can be downloaded here: Nostalgia Slideshow. (Right-click on the slideshow and choose Presenter View to read the text with each slide.) Footage of me speaking, filmed by Tanya DePass of I Need Diverse Games, can be found here: Tanya's Twitch Channel.

1

Hello, and thank you for coming to my talk, Nostalgia: An

Enemy to Progress.

The purpose of this talk is not to say, “Nostalgia is bad, mmmk?” Rather, it is just one factor among many that can lead to practices in game development and design which marginalize potential players, both in terms of representation and accessibility. And hopefully, by the end of this talk, you’ll understand why I decided to use this pixelated heart for your opening impressions.

I do want to warn you that while I am not an academic, a scholar, or an academic scholar, I consulted a number of academic essays and papers for this talk. I’m sorry, but sometimes talking about systems and power structures is actually challenging to do without sounding like you just might have a PhD. My goal is to average the speech in this talk to “probably quit grad school and works in telemarketing” to make it easier to digest.

Also, I will be discussing racism and sexism mostly, but my presentation does not include images of violence taking place.

For now, let’s get on with it.

2

Much of my own video game playing history begins in the late

80s/early 90s. During that time, a new mall was built near my home in Freehold

Borough, NJ, and with it came an arcade, called Time Out. Sitting at the front

of this arcade was The Simpsons arcade game. Like many kids at the time, I would

beg my mother for some quarters or even whole dollars to go play in the arcade

while she shopped or waited patiently in the nearby food court. It wasn’t until

she gave me $5 at once that I was able, with occasional help from random

players, to beat the game. It was very much the same for the X-Men arcade game,

which replaced The Simpsons at the front of the arcade. I didn’t just fall in

love with this game; it actually began my interest in the X-Men generally,

particularly with Storm, the Beautiful Windrider, with whom I’m still obsessed.

Oddly enough, this didn’t get me into comics at all, so I didn’t get my next

X-Men fix until the premiere of the Uncanny X-Men cartoon on Saturday mornings.

3

Of course, I also played games at home and in other people’s

homes. The first game system I owned was the original Gameboy, and my favorite

game on it was Kirby’s Dreamland. My nostalgia for Kirby’s Dreamland is so

strong that all the sounds on my phone are actually sounds from the original

cartridge. Thanks to a new neighbor who moved in around 1989 or so, I got

access to all his video games systems: various Ataris, the NES, and the Sega

Genesis. Inspired by him, I eventually got my own Sega Genesis (as a Chanukkah

present). One of my favorite games to play on that was Eternal Champions, a

fighting game that groups people from various time periods, and, as it was

post-Mortal Kombat, included ways to kill your opponents, called Overkills,

using the environment. These were my favorite things.

Further away lived family friends, whose children, two brothers, I enjoyed playing with and formed a close bond for a number of years. They eventually got the SNES. I was there for the first weekend when they opened it up and dived in. The three of us would often alternate as to who would be next to guide Mario to the goal of the current stage. Diving into the secrets, like Star Road, was so new for me compared to more linear games, including previous Super Mario Bros. entries. It is a game I probably feel the most nostalgia for because it was (and still is) excellently designed and genuinely fun.

4

However, I don’t experience nostalgia like developers,

publishers, and PR seem to want me to. When it comes to my gaming experiencing,

I only feel nostalgia for the specific games I played, meaning that revealing a

game that plays like, looks like, or otherwise resembles a game I loved in the

past doesn’t move me. I only want the specific thing I had once, and in many

cases, I still do or I have access to them but without diving into the retro

game collecting scene, which is a beast of its own that I don’t need to discuss

today.

5

No, regarding my nostalgia and how it operates, I think this

quote gives a good sense of what is and is not operating like “normal”

“On a basic level, recalling these positive memories simply puts us in a more positive mood[…]On a more complex level, recalling these experiences makes us feel a stronger sense of social connectedness with others. We’ve done some research looking at what people usually describe as a ‘typical nostalgic experience’ and find that people typically think about positive experiences in which the self is the protagonist, but they are surrounded and interacting with close others.”

(I should note that across the entire article, his first name was misspelled three times, so I just Googled what it actually is.)

Cordaro here is stating that nostalgia operates as a function of situating ourselves within our memories of interacting with others. And I think that’s where my personal history diverges and ultimately limits my nostalgia. Although I spent time with and played video games with my neighbor, we didn’t get to spend that much time together, and we never got close. We were mostly proximal, and though to this day I still care about his wellbeing, I can’t say he was one of my best friends. When I was in school, I was often made fun of for being smart, basically pushed around for being a nerd. And when some of those jerks grew some hormones, before I was even attracted to anything, I was called a faggot simply for just being. Although it never reached the point of physical violence, it was traumatic enough that I didn’t even consider my sexuality until I was attending a high school in a completely different town with completely different students.

To that end, I didn’t have many friends. My closest friend in town lived in whatever you’d call the Unitarian Universalist version of a home that believes the devil makes work for idle hands to do. He was maybe the busiest person I knew every year of school. So I played games alone. Despite owning Super Street Fighter II, Eternal Champions, and Mortal Kombat for my Genesis, I often played these games alone. Because I wasn’t good at any of them, I’d just set up two-player matches where I practice fireballs and the like against an unmoving opponent.

And what of my time playing Super Mario World with my friends. Well, like all the other games, my nostalgia begins and ends at the game playing experience, because overall I’m trying to forget how often I witnessed the older brother grow angry or violent against his younger brother, putting him through some kind of toxic masculine ritual whereby he’d “train” the younger one to fight through tearful pleas. Did it happen every time? No. But eventually, in high school, when I finally started to build a network of friends, I abandoned this pair wholesale and with them, these memories of being surrounded by others.

6

So what is nostalgia anyway?

Dictionary.com defines it as “a wistful desire to return in thought or in fact to a former time in one's life, to one's home or homeland, or to one's family and friends; a sentimental yearning for the happiness of a former place or time.” It comes from the Greek roots, Nost, meaning to return home, and algia, which is to feel pain. This may, in many ways, seem extreme, and it’s possible your own personal definition of nostalgia does not actually involve pain. But it does always involve a desire to return to a memory that is not situated in the present.

7

"When people are nostalgic, they are reflecting on

personally significant or momentous past experiences. These memories also tend

to be largely positive, though a tinge of sadness is often present; nostalgia

is often a little bittersweet.”

8

Nostalgia is in a way a form of escapism. If we can tap into

it, we can ignore what hurts us now in favor of something that makes us happy.

If the idea of escapism sounds familiar within this realm, it should, because

for a lot of us, gaming is also a form of escapism. And this doesn’t require

the gatekeeping moniker of “hardcore gamer” to accomplish either. Regardless of

the game, you cannot otherwise be transfixed on an important or relevant task

in your life. For however long, be it a World of Warcraft campaign, a mission

in Gears of War, or a level in Candy Crush, you are bargaining with your time

and cognitive ability for a break.

9

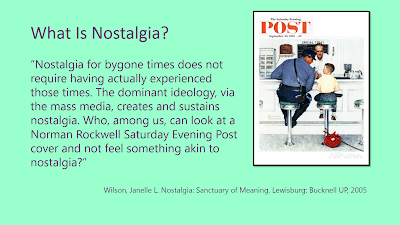

Combined with nostalgia, video games present a unique

opportunity for companies to utilize branding and marketing to make us “return

home” and “escape” by exploiting our desire to repeat interactions that we

still hold dear. Furthermore, by presenting a distilled picture of our own

pasts and the pasts of others, they can sell us nostalgia that is wholly

unrelated to us. Janelle Wilson, in Sanctuary of Meaning, writes, “Nostalgia

for bygone times does not require having actually experienced those times. The

dominant ideology, via the mass media, creates and sustains nostalgia. Who,

among us, can look at a Norman Rockwell Saturday Evening Post cover and not

feel something akin to nostalgia?”

And it’s true. Though various forms of media, including movies, books, artwork, and video games, we have been permitted access to histories that do not necessarily belong to our own experiences.

10

We can explore them and build desires off of them that are

entirely out of context. Take old-fashioned fashion for instance. Through

period piece films and Renaissance Faires, we are permitted the indulgence of

wanting not just to dress like people used to but to be surrounded by that

dress, to live in a society of fashion that is incredibly anachronistic to now.

Elizabeth Guffey writes, “At best, retro recall revisits the past with acute

ironic awareness; self-conscious in its recollection, retro revivalism lays bare

the arbitrariness of historical memory. At its worst, retro pillages history

with little regard for moral imperatives or nuanced implications. As entire

periods of the recent past are introduced into the popular historical

consciousness through retro’s accelerated chronological blur, we risk

incorporating its values as well.”

And what are the moral imperatives and values Guffey is referring to?

11

Context.

The nostalgia we are forced to consume often comes from a privileged perspective. The fact is we do not all experience nostalgia in the same way, but our identities and our histories ensure nostalgia does not have a one-size-fits-all benefit. Specifically regarding the images here, while privileged white women can think of how beautiful the dresses were in the 19th century and before, longing to just spend one night at a ball filled with gorgeous gowns, the treatment of people of color, in particular black people, generally remains an afterthought. This isn’t just because privilege clouds the minds of those who have it, but the media we consume constantly reinforces the personal drama and endeavor, one that eschews historical accuracy depending on its relevance to the story being told. It’s disingenuous, and it both thoughtlessly and sometimes purposefully makes its way into our games.

Regardless, just as a black woman cannot be expected to look at images of old gowns and feel nostalgic, women generally can’t be expected to feel nostalgic for the world of men, queer folks can’t for the world of heterosexuals, and trans people for the world of the cis. It’s not that marginalized people cannot empathize with media featuring those more privileged than them – quite the opposite actually – but we (including myself as a gay Jewish immigrant) have to further contort our memories and our principles to make them palatable when they unwittingly cross the line and remind us of oppression. If we can still feel nostalgia after that, it’s because we’ve become highly skilled at navigating an environment that seemingly will never belong to us.

12

What is this?

This is a list of games released last year just up through September which are either sequels or continuations of known franchises. I got really tired and depressed and sleepy at this point. Certainly, we’ve all felt like we get lots of sequels, but beyond criticizing the basic creativity of the developers on these fronts, it’s rare that we consider what these sequels are conditioning us for.

Both Rise of the Tomb Raider and Uncharted 4: A Thief’s End continue stories about white imperialism, exotic tourism, and rather unquestioned cultural pillaging. Star Ocean, Atelier Sophie, The Banner Saga 2, and Attack on Titan don’t feature black people or people of (normal human skin) color. Street Fighter V, regardless of its gutted campaign, still features a roster of racist stereotypes and sexist exploitative dress for female characters. And until Pokemon Sun and Moon came out in November, Pokemon Go continued the tradition of not allowing black people to create avatars with skin like theirs. Regardless, the hair options for Sun and Moon are not diverse, but maybe next time!

My point is that although the technology driving these games and their budgets may be moving forward, creating a sequel often comes with implicit permission not to do so in terms of representation. And this is also evident in video game remasters and re-releases, which solely improve the technology driving the game but little else about them.

13

And that brings us to Nintendo.

OMG.

So Nintendo is particularly egregious in their practice of releasing sequels to their franchises. Aside from Splatoon, Nintendo has released games in the Mario, Zelda, Star Fox, Metroid, Super Smash Bros., Fire Emblem, and Kirby series ad nauseam. They are famous for releasing their own properties, even if they aren’t always the first-party developer on them. However, with these franchises further digging into our cultural present, their own pasts become distilled and untouchable. Mario and Zelda, as portrayed here, are treated as if they were developed in a cultural bubble, that nothing has changed around them. It is a compression of our history with them where each game is expected to remind us of the last one, the one before that, and so on, taking us as far back as Nintendo can get us towards our childhoods.

But during those childhoods, and well into the recent past, games were advertised explicitly for one gender: male.

14

“In the 1990s, the messaging of video game advertisements

takes a different turn. Television commercials for the Game Boy feature only

young boys and teenagers. The ad for the Game Boy Color has a boy zapping what

appears to be a knight with a finger laser. Atari filmed a bizarre series of

infomercials that shows a man how much his life will improve if he upgrades to

the Jaguar console. With each "improvement," he has more and more

attractive women fawning over him. There is nothing in any of the ads that

indicate that the consoles and games are for anyone other than young men.”

The more Nintendo releases iterations of their “classic” franchises and stick to that as their dominant business plan, the more they reassert themselves within a culture that exclusively targeted boys with advertising and now targets men with nostalgia. But clearly women and people of other genders caught on and played these games, marketing notwithstanding, and part and parcel to that was the desire to be included.

15

Before Nintendo revealed the actual identity of their next

console, the Switch, and before Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild had a

subtitle, there was quite a bit of discourse about changing the hero of these

games, Link, to be female, because Link, much like tofu, existed to absorb the

flavors of the story around him but lacked personality otherwise. Thus, it was

concluded, the character could be anybody. However, in a rather engaging

rebuttal, former Action Trip EIC, Keri Honea, writes, “But why swap the gender

of an established character in the first place, when there are plenty of other

options to give the series, or any other series, a woman-centric spin?...For

instance, The Legend of Zelda series already has two women part of the tale:

the Princess Zelda and Impa, Zelda’s bodyguard and handmaiden from the Sheikah

warrior tribe. Twilight Princess and A Link Between Worlds also both introduced

new female characters, Princess Hilda and Midna. There are plenty of women for

the series to choose from if Nintendo wants to make a woman the lead hero in a

future Zelda game. Why not have Zelda save Link? Or tell a tale starring Impa?

Or what about Impa and Zelda ala Thelma & Louise?”

And frankly, the reason may just be because Nintendo has little faith in changing up the formula that has worked over and over and over again for them. Way back in the 80s, when they switched up the formulas for both Mario and Zelda – that is, Super Mario Bros. 2, a re-skin of another game, Doki Doki Panic, and Zelda II: The Adventure of Link, which turned the top-down adventure into a side-scroller – they experienced minimal success. And these were only gameplay changes. Representation seems to be a bolder challenge for them as their beliefs have clearly become antiquated.

16

However, Nintendo did eventually give the famed damsel in

distress, Princess Peach, her own game. (Sorry, Zelda.) But, it comes with some

noticeable caveats. The story, which sets up the premise for Peach to rescue

Mario, Luigi, and her kingdom, is that one of Bowser’s henchmen get ahold of a

scepter that, when waved around, turns everyone into an emotional wreck.

Completely distracted with emotions, nobody seems capable of coping. Peach, who

wasn’t around for this spell, takes it upon herself to restore order in her

kingdom, but that doesn’t mean she is without emotion. In fact, her abilities

for getting through the game are tied to these emotions. Joy sends her

floating, gloom makes her cry tears that could fill an empty pool and increase

her speed for running away crying, rage surrounds her in flames, and calm can

regenerate health. Although one could argue that having a hero who is in touch

with their emotions is a positive sign, this doesn’t fit that vision so easily.

Her first game, and Peach is fulfilling a trope of women who not only get

emotional at the drop of a hat but can wield those emotions to manipulate their

surroundings.

Furthermore, the course of the story doesn’t even focus on her. Her main weapon for dealing with baddies is her famed parasol, but in this game, it gets a biography. It’s inhabited by the spirit of a boy, Perry, who was transformed by an evil wizard. As Peach defeats the final boss in each world, instead of focusing on her journey, we get to see flashbacks in the forms of Perry’s dreams as he recovers his memories about his situation. Peach just sleeps by the fire, happy just to be there, apparently.

Next, Tomodachi Life. Nintendo created a game for players to have fun antics and create stories using their Miis, player avatars exclusive to Nintendo’s social ecosystem. However, it was not long before the game’s release that it was revealed that homosexual relationships would not be possible. After player outcry, Nintendo released this tone-deaf statement: “Nintendo never intended to make any form of social commentary with the launch of Tomodachi Life. The relationship options in the game represent a playful alternate world rather than a real-life simulation.“ Although well-meaning people can determine what Nintendo Nin-tended to say with this statement, their actual message ended up being one that told the queer community that their relationships and their marriages, rather than being normal parts of life, are social commentary and don’t have a place in their game. It is apparently not “playful” to simulate those relationships. This is, of course, laid on top of the cissexist gender binary that’s possible for Miis anyway.

17

Although Nintendo represents the top tier in rehashing their

own IPs repeatedly to play on players uncritical nostalgia, they are not the

only ones guilty of it. The fact is any developer who, often pushed or

contractually obligated by a publisher, decides to create an iterative

franchise, is susceptible to the same mistakes. Five games into the Grand Theft

Auto main series (excluding portable titles), and women still aren’t playable,

and are in fact still portrayed in a sexist/misogynistic manner. Despite making

serious improvements with their last entry in terms of representation, the

Assassin’s Creed series has only featured one main entry with a playable person

of color, whited down with the name Connor and following a debonair white

Italian man who had three to himself. Aveline and Adewale, two black

characters, Shao Jun, a Chinese woman, and Arbaaz Mir, an Indian man, were only

playable on lesser-played portable and DLC games.

The Halo series has now committed to Cortana being inexplicably clad in a techno-swimsuit. And although there appears to be some emotional nuance in the upcoming God of War game, every iteration of that series has featured having sex with women for a Playstation Trophy and some health along with other problematic portrayals of women.

18

What I’m trying to convey with this portion of my talk is

that every sequel that is released capitalizes on the nostalgia of its

established audience. Each new entry that only incrementally improves on the

previous resets our expectations back to the first time we played a game in the

series, and it reinforces the bubble these games are assumed to have been

developed in. Repeated issues with representation end up being excused with,

“Oh, well, I mean, that’s just Game Series for you,” or “Didn’t they have a

strong female character in the last one?”

“This continued reliance on the games’ past, and the players' experience of that game, is the sine qua non of contemporary games culture, and this dynamic forecloses the potential for the creation of a critical distance between the present and the past.”

Sequels that don’t change up their formulas, particularly in areas of representation, force players to uncritically accept them, and those left marginalized by repeated offenses are just expected to wait on the sidelines or join in and shut up.

19

Before continuing to the next section, I’d like to also

include this quote from an excellent essay by Megan Condis.

“We idealize the entertainment of our youth as apolitical, carefree fun because, as children, we ourselves were carefree. We were unaware of the political currents that were always running through our favorite films and tv shows. When we return to these texts, we seek that same innocent, cheerful mood they used to put us in as kids. We resist being dragged back into the concerns that plague our adult world: gender, race, sexuality, class, power, violence, injustice. We forget that they were always there, lurking in the background, inescapable.”

I recommend reading the entire essay.

20

Although I’ve given you an idea of how nostalgia works

through iterative series, even ones that stand alone or break the mold can

utilize nostalgia in exploitative ways. However, simply performing what I’ve

dubbed “Historical Tourism” can be fraught with issues. Despite any beliefs we

may have that developers “didn’t mean it” when they manage to offend an

audience, the point is that focusing on the past through a lens of privilege

will probably yield such a result.

Mattie Brice writes, “Game design is political. Not just the field (that’s another minefield to go through), but the designs that makes up each game. How a game allows a person to interact with it is extremely loaded with discriminatory politics, because they are usually made for particular players in mind.”

21

In order to explore this, I’ll discuss explicit nostalgia

and implicit nostalgia. Put simply, explicit nostalgia includes direct

reference to the past, such as a game taking place during WWII, and implicit

nostalgia includes references to the media’s past, such as through pixel art.

I’ll go through a number of games that include these references and explain

where they may have gone wrong if it’s not completely obvious.

22

I honestly believe Bioshock Infinite is so perfectly

problematic. Like it’s almost unfathomable how off the rails it went with its

story into outright bullshit. To set up for you, Bioshock Infinite takes place

during an alternate history where people who worshipped the US’ founding

fathers built a city in the sky to double down on their religion and racism.

The setting itself is nostalgic enough for turn of the century architecture,

but the game presents various anachronisms to make the audience think, “Oh, I

remember that.” For example, there’s a scene where Elizabeth, the “girl” you’re

tasked with saving, opens a portal to France when they were showing Revenge of

the Jedi in theaters. A number of the vocalized songs you hear throughout the

game come from places in our own history that are not the 1920s, such as the

Beach Boys’ “God Only Knows.”

And in this world, racism exists. How unfamiliar, right? Black people are basically slaves in the sky, and a rebel movement, the Vox Populi, is being led by Daisy Fitzroy, former servant to the city’s matriarch. And it’s not long after meeting her that the story gives up on its pretenses of doing our historical past with racism right. Much of the media for the game made it seems as if, despite playing as a white man, you would join and help the Vox Populi. However, there comes a scene where Daisy is threatening a white child, exposing, I suppose, how she’s somehow no better than her oppressors, and she is killed by Elizabeth. After this, the Vox Populi turn on you violently as a traitor, creating this dissonant “Both sides are bad” rhetoric that’s bitter to taste, and you are forced to kill people of color now to survive to the next level.

But really the game went wrong very early on with this interracial couple. Before any of the game’s action begins, you attend a fair where some lucky person wins the opportunity to throw a fresh, red apple at this couple, tied up on stage. You are the winner, and the game presents you with a choice, to either throw the apple at the couple or at the announcer goading you into doing so. Due to how the scene plays out, you don’t actually get to throw the apple at anyone, which begs the question: Why would the developer give you a choice? If there was really any bold or even true statement to make about race relations in the early 20th century, your character would just not be given that opportunity. Otherwise, it opens the field for racist players to just be racist players whether or not they get to see the results of their choices.

The game makes no attempts at even drawing parallels between historical and contemporary (2013) society. Racism is a backdrop in another white guy’s super important journey.

23

Wolfenstein: The New Order is another mishap when it comes

to garnering empathy through historical tourism. Also taking place in an

alternate history, the player once again assumes the role of savior white guy.

However, compared to Bioshock Infinite, he actually succeeds. Like he actually

helps. Kudos to him.

In this history, the Germans actually won WWII and managed to spread throughout the remainder of Europe. It’s not that I don’t believe that such a conjecture is bad in and of itself, but one must tread incredibly carefully. To that end, the basic format of the game nullifies that, being a high action first-person shooter. It falls in this combination category of explicit and implicit nostalgia Ryan Lizardi wittily refers to as “How I Learned to Solve Every Historical Crisis with My RT Button.” Call of Duty, Medal of Honor, multiple first-person shooter games and franchises do this, where they take the commonly understood premise – the Germans were really bad – and creates a scenario by which players can fix everything, either by repeating the events of WWII as a personal drama, one removed from the people who suffered it, or by creating new scenarios for them to be even better at killing Hitler. Furthermore, shooters and action games in general are guilty of using implicitly nostalgic control schemes. Although on the surface it makes sense for developers to use similar control schemes and gameplay mechanics for similar games, a portion of players is always left out by this rigid devotion: those with different physical, motor, and cognitive abilities. You’d be surprised at how many devs, simply copying what they think worked well before, fail to include remappable controls, alternate controller support, color blind modes, and other features that could help a larger audience come to their games. Anyway…

The problem I find with this particular game, identifying as a Jewish immigrant and descendant of Eastern European Jews (BTW anti-semites, thanks for the influx of swastikas and bomb threats), is that it allows a primarily American audience – Bethesda is an American company – to feel like the hero they were taught America was in the war and absolve themselves of their historical past, one where America was full of anti-semites and Nazi sympathizers, one that turned away a boat full of Jewish refugees, leaving many of them to die, much in the same manner politicians wish to do to the Syrians now. That game, the one where non-Jewish Americans are forced to deal with the consequences of their families’ apathy, doesn’t exist.

Forging on, as an absolutely hilarious demonstration of my point, players are put in a concentration camp. I took this screenshot of some gameplay from the first 30 seconds of walking through the processing chambers, and I’d like to point out the symbols on the bottom. They are symbols for health and armor, and they appear during this solemn moment, unable to wait a minute. Eventually, you, who are undercover and looking for a particular prisoner, have to cause a distraction, change outfits with another prisoner, and then pursue and kill a maniacal monster who is known for randomly slicing up prisoners with his knife. During a scene where he catches you and ties you down, he slices you up, eventually plunging the knife into your chest.

But you have something millions of Jews and the dead bodies you crawled over to get into this chamber didn’t have: regenerating health. *sigh*

You know, I get what the developers were trying to do, but the fact is, when you make a game of the Holocaust, you trivialize it. If you want to look back there as inspiration for your game, you need to do so critically and thoughtfully, which is basically what Brice was getting at in her essay.

24

In fact, Germany forced Bethesda to remove all Nazi

references in the game, despite the known history of the franchise. Writing

about it, Edward Smith states, “The ban isn't an affront to free speech. It's

the German government, quite rightly, recognising that videogames, particularly

Wolfenstein, aren't equipped to handle and depict this subject matter with the

sensitivity it deserves. Wolfenstein sees players killing German soldiers using

a laser gun. The plot involves a kind of Rob Zombie-type Third Reich, which

creates "the world's biggest atom bomb" and drops it on New York

City. Real history, this is not. And frankly, if Wolfenstein is going to

re-appropriate the still recent and very horrifying events of the Second World

War into something so ham-fisted, it seems reasonable that it be banned from

directly referencing both Nazis and concentration camps. These aren't topics

that you can play around with and amplify. Some things aren't suitable for

being turned into toys.”

And I’m inclined to agree.

25

Ah, Red Dead Redemption, or Grand Theft Horse. That implicit

nostalgia I mentioned clearly led to its gameplay, shaping an experience that

reels in fans of Grand Theft Auto to feel comfortable, familiar, and safe even

in the American frontier. Thus, it also invites this uncritical peek into

America’s past.

Like with tying up women and putting them on train tracks. Originating in 1867 in a short story and brought to film in 1913, Americans with any memory of old media, as communicated to many of us as children through Warner Bros. cartoons, should remember the old trope of tying a woman to train tracks. Except, proper total recall would tell us it’s only the dastardly villain who does this. Instead, Rockstar obfuscates our nostalgia to allow the player, who is not supposed to be the villain, to do this repeatedly, the only punishment being a bounty being placed on the protagonist’s head, which is easily resolved with some money.

And then there’s Mexico. Somehow, our hero, John Marston, manages to use his whiteness to singlehandedly remove a dumb military leader from power for a fairly disorganized band of rebels. And he can find a poncho while he’s down there, something to wear on the playa!

Again, it’s nostalgia used to present more tropes and create exploitative gameplay possibilities.

26

Red Dead Redemption also eventually features a prominent

Native American character, Nastas. Nastas is working for a white scientist by

the name of Harold MacDougal, who repeatedly condescends to Nastas as if he

were stupid, venturing into phrenology. Their relationship is one where racism,

which was common at the time, is presented to make the contemporary player feel

superior and above that. But despite this dynamic, neither John Marston nor the

player themselves can actually do anything about the racism. They can simply

observe it until Nastas is shot in a later scene, MacDougal memorializing him

with “May you find God,” a final spit on his grave if you ask me.

This dynamic I speak of, one where the game sets up situations for you to feel superior or removed from the problems (sexism and racism) of that era, leads to some more choice quotes from Mr. Lizardi.

“…playing Red Dead Redemption is not like playing and re-enacting some radical past that makes players discuss and take a critical stance towards history, but instead operates like a myriad of other contemporary games; it is a new game costumed in a historical skin.”

“Instead, the past-centered Western narrative is simply used as a convenient framework upon which to hang contemporary goals, values, and ideologies.”

“The result is a narrative that validates the goals and values of the present while simultaneously conflating them with the past.”

“...a problematic past is created to serve the present through fixing players' gaze backwards at an uncritical, presentist history.”

Essentially, if the game actually had something to say about society in these times, it would offer the player opportunities to resolve it, not in a feel-good 30-minute special episode sitcom sort of way, but in a way that allows the action to be performed without absurd levels of acknowledgement. Players wouldn’t get experience points, a new weapon, a trophy, or the fabled Ally Cookie.

27

Next, indie game developers, even super niche ones, are

susceptible to the kind of historical tourism that fails to take real life

situations into account. In Sunset, by Tale of Tales, a Kickstarter project I

actually backed, you play a black woman from Baltimore working as a maid in a

fictional South American socialist country. From the game’s description on

Steam:

“It's 1972 and a military coup has rocked Anchuria, a small country in Latin America. As a result, you, Angela Burnes, US citizen, are trapped in the metropolitan capital of San Bavón. Your paradise has turned into a warzone. To make ends meet, you take up a job as a housekeeper. Every week, an hour before sunset, you clean the swanky bachelor pad of the wealthy Gabriel Ortega. You are given a number of tasks to do, but the temptation to go through his stuff is irresistible. And what is he up to? As you get to know your mysterious absent employer better, you are sucked into a rebellious plot against the notorious dictator who rules the country with an iron fist.”

The goal of the game, as indicated by the developer during crowdfounding, was to finally create a game that explores war from the perspective of someone who’s not the brave soldier fighting in the heat of battle. Instead, you’re playing someone swept up into the society created by the ongoing war. On top of cleaning or rearranging things, you have the ability to write diary entries, learn to play the piano, and leave notes, either romantic or rebellious, for your employer, with whom you can form a romantic relationship.

Say Mistage, a former social media manager for Phoenix Online, actually lives in socialist Venezuela as it’s being torn apart, and she took a number of issues with even the basic premise of the game.

28

In the game, Angela fled to this socialist country because

she was attracted to its ideals, those of socialism. However, despite how much

socialism as an ideal gets right, it’s important to reflect on its historically

botched implementations and learn from them.

Mistage writes, “It is my understanding that egality is a representation of social equality, however, pretending that exists in socialism clearly shows a misguided textbook interpretation of the painful reality socialism is in practice. Socialism espouses collectivist principles, but in reality it is a redistribution of wealth controlled by the government that does not showcase social fairness, but instead redistributes the misery.”

What she is getting at here is that despite the ideals of socialism, we already have real world evidence that the reality has not been as pretty for many people, and romanticizing these notions even from the get-go can be irresponsible and offensive. In Sunset, although Angela is affected by the eventual war, and she can witness it outside the window on some occasions, the game continues to settle this condominium for the player as a retro escape, romanticizing this small two-floor world through the nostalgic lens but creating a fantasy Mistage describes could not even exist due to the dynamics of socialist governments – those that led to her employer having a condo, even those that led to her losing her qualifications from her degree and becoming a maid, are altogether false or unlikely.

She continues, "These unrealistic assumptions of economic equilibrium directly affect social values, it deteriorates progress creating budgetary depravation and political tyranny. There is no justice in micro-managing what people eat and buy, no matter what equitable ideals you hold it up to - it is brutally dishonest. There is no glamour in celebrating flawed ideas that have proved to fail time after time; journalists praising Sunset as a 'war-like experience', are just as misguided as obsolete 'intellectuals' that pursue this lie.“

29

But is it all bad, Gil? Is nostalgia just a very bad, no

good thing that all developers must divest themselves of?

No, of course not. Not to create any kind of false balance here, but I do want to precede my conclusion with some works that I think manage to subvert the uncritical nostalgic lens.

Treachery in Beatdown City by Shawn Alexander Allen and Nico Marcano is not out yet, but a lot of development work has been done. It might even be playable somewhere here. It is an old school beat ‘em up style game that features playable characters of color and is meant to resemble the developers’ understanding of the non-Manhattan boroughs of New York City, which are generally less featured in games. From listening to talks, both developers have carefully worked the dynamics in the game so that, for example, women aren’t treated in sexist manners or that race does actually get commented on thoughtfully. You can even find Elizabeth Simin’s Gaming’s Feminist Illuminati logo somewhere in there.

30

Fez, by Polytron, headed up by the infamous Phil Fish, is

what I feel a fantastic example of nostalgia use. The game uses 2D pixel art

graphics like many indie games do nowadays, but Fez was different in that

players actually had to rotate their environments as they would exist in 3D

space but deal with the 2D orthogonal views resulting from these rotations.

Although the game initially resembles 2D side-scrollers of the past, it’s

actually a creative 3D puzzle game that requires a lot of critical thinking to

discover all of its mysteries. Also unlike old 2D side-scrolling games, there

is no time-limit and the game requires no reflex use, increasing accessibility

for players with differing cognitive and motor skills.

31

One of the first essays I read to even prepare for this

presentation was “'The Nostalgia Question' And Feminist 8-bit Game Hacking” by

Rachel Simone Weil. In it, she discusses her own relationship to nostalgia and

how it relates to her development practice, particularly at game jams.

Accustomed to doing cart hacks, whereby a developer modifies an existing

cartridge-based game from the NES or Gameboy, Weil has managed to impress her

childhood upon a medium that was likely not as welcoming of someone like her.

Hello Kitty Land re-skins Super Mario Bros. to be Hello Kitty-themed, questioning the idea of what that game could’ve been or how it would’ve been received with the popular Sanrio character instead of the Italian plumber. Faxie’s Unicorn Blast is a side-scrolling space shooter that uses a cutesy unicorn instead of a spaceship. Electronic Sweet-N-Fun Fortune Teller is horoscope game that would otherwise have not existed in the 80s. And Look at Me Now, I’m Burning Up the Steel is an interactive artwork that puts together images from girl’s board games and networking paraphernalia.

32

In her own words: “How might women uniquely interpret and

reinterpret 8-bit visual language from an era in which gaming was primarily

conceived of as a boys’ pastime, in which very few games were marketed to

girls, and in which girls were often discouraged from being present? Can women

feel nostalgic about games they were not permitted to play as children? What

does it mean to depoliticize or repoliticize a device called “Game Boy?” For

me, focusing centrally on nostalgia and gaming has not been a cheap gimmick or

artistically vacuous, but rather a vitally necessary form of critique,

rebellion, and reconciliation.”

Weil poses some thoughtful questions. If games were marketed for boys, how are women supposed to look back nostalgically at the NES age? I recommend reading her essay, but Weil mainly posits that by taking the things that do make her feel nostalgic, the girly toys of her past, players are forced to reconcile the alternate history she’s in effect created.

33

So I return to this pixel heart from the opening slide of my

presentation. What does a heart mean in gaming? Typically health for our

often-male hero. But isn’t it also a feminine-coded object? How did it live a

double life all these years?

34

As I stated earlier in this talk, due to the intersections

of our identities and other unique factors during any moment in gaming history,

we are not all on the same footing when it comes to nostalgia. We can’t be

nostalgic for the same things or in the same ways.

So I had to think after reading Weil’s essay, how does gaming actually treat girl things? As you probably already know, not well. I mean, it’s not like any Hello Kitty game made any top ten lists. That’s not just because gameplay in girly games were bad – and they often were – but developers were not given the budget, the focus, or the marketing power to really bring girls quality games. And of course, this has an impact on little queer boys and trans and non-binary children who may have desired any new way to express themselves.

Thus when it comes to the role of girly elements in games, evidenced here by Whimsyshire from Diablo III and Mr. Toots, the laser farting unicorn from Red Faction Armageddon, they’re included as jokes, comic relief from the seriousness of their parent games. Thus, being serious or productive in any manner is relegated to the binary male. Girls and their things were jokes, and that idea has clearly been carried via the various forms of nostalgia I’ve described into modern gaming, and it perpetuates itself ad infinitum.

35

I hope that I have successfully demonstrated the perils of

nostalgia as it applies to gamers. We are diverse in this room and we all have

remembered pasts that differ from each other. But one thing that’s clear is

that for most of us attending this conference, game developers and publishers

have been trying to appeal to our nostalgia for decades now without actually

trying to appeal to our humanity. When it comes to most mainstream games, there

is still one target: the cisgender heterosexual white male among various other

intersecting privileges.

As long as the gaming industry and even we as consumers allow the poorer aspects of nostalgia to exploit us while appeasing their target demographic, games will only ever incrementally change as their initial point of reference keeps being recalled uncritically and unironically. This exists in other forms of media as well, notably films and comic books, - video games do not exist in a bubble – and as long as we allow our society to uncritically think back to happier, simpler times, we are allowing them to happily and simply look back at times when our various forms of oppression were a lot fucking worse.

36

Thank you.